- Homepage

- Author

- Alfred Bruneau (3)

- Anatole France (3)

- Auguste Maquet (3)

- Beydts (louis) (4)

- Camille Mauclair (3)

- Charles Monselet (3)

- Chateaubriand (5)

- Ernest Daudet (3)

- Henri Barbusse (3)

- Jean Couty (3)

- Jean-léon Gérôme (5)

- Louise Read (4)

- Marcel Proust (5)

- Paul Chabas (4)

- Paul Meurice (3)

- Proust (3)

- Roger Martin Du Gard (4)

- Salomon Reinach (3)

- Sully Prudhomme (7)

- Violette Leduc (4)

- Other (3994)

- Binding

- Condition

- Era

- 18th Century (11)

- 1900 To 1960 (60)

- 1930s (4)

- 1960s (5)

- 1970s (7)

- 19th (5)

- 19th Century (48)

- 20th Century (15)

- Beautiful Era (12)

- Belle Epoque (49)

- First Empire (8)

- Nineteenth (19)

- Nineteenth Century (11)

- Post-war (21)

- Restoration (17)

- Revolution (4)

- Roaring Twenties (28)

- Second Empire (21)

- Second World War (5)

- World War Ii (9)

- Other (3710)

- Language

- Theme

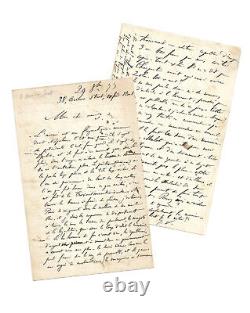

Jules Valles / Unpublished signed autograph letter 1877 / Commune / Exile / Trilogy

" to Aurélien Scholl [London], October 29th, 1877, 6 pp. In-8° in dark brown ink with very tight writing Laid paper, watermark "Ivorite" Some crossings out and ink smudges by Vallès.

Distant and disillusioned with French politics, Vallès reveals in a long and superb letter, completely unpublished, his editorial ambitions for his autobiographical trilogy. We transcribe here only a few fragments. The future belongs to the phlegmatic, as Napoleon said. It's true when it comes to pretenders.

It's false when it comes to deputies - and at some point, in the rain, in the storm, we must hear the thunder of Mirabeau. We won't hear it anymore. Parliamentarism has pockets too full and heads too empty.

If we dare to poke with the bayonets the gold that bulges in these fat bellies, the three-hundred-sixty-third [allusion to the 363 manifesto] is done for. Through the infinite mist of London, I glimpse Paris bleeding under the softness of its blue sky, and I see the corporals quarreling through the streets over the testons of parliament, the idols of legality.

Who will dare the coup d'état? Faced with the retreats of the great suffrage, faced with the asinine tactics of opportunism, on the eve of a December 2nd [allusion to the Coup d'Etat of Napoleon III on December 2, 1851] more dishonorable than the first, or facing a bourgeoisie as anti-socialist as on December 2nd, I think of letting my political hopes sleep and returning full-time to my profession. I am writing to you under the impact of this painful violation.

An editor - who is no longer one - was supposed to be in London four days ago. He brought me the scent of bookstores and tried to intoxicate me with it. He argued that I would now succeed as a novelist. By God, I have long thought of locking myself face to face with what I have seen, to photograph it in the tawny light of my time, and I will only ask to shoot the enemy through a book, which would vanish like the African undergrowth behind which the Arab would murmur "French dog!" and aim to kill the sentinels.

I would fire sheltered by feeling, under the guise of passion or irony. But I had to write this to you twenty times! Let's talk in a less inspired tone and put the dots on the i's. Durand did not seem to find me too reckless in thinking about the following combination: to make a deal with Charpentier [publisher among others of Zola and Maupassant], for example; by which he would undertake to provide me with supplies for a necessary time to build my work, to finish my Les Misérables.

I have the plan, the material for a great novel in three more or less distinct parts, which would represent the history of the grotesque and heroes, the bold of idea or crime since 1848. Last from 70 until May 28, 1871. With what I have already prepared, I need two years or more to carry out this campaign successfully. To live during these two years, I need 300 francs per month. If a publisher wanted to own my work, he would only have to give me this annuity [.] Do you see anyone who would be willing to risk these few coins against a copy? I would be given my 300 francs on so many manuscripts.

Nothing to lose, everything to gain. I would sell it as desired - either firm to be published immediately in volumes, as Les Misérables were published, or serializable [.] The book would be worth ten times the advance made, if it were successful - what am I saying: twenty times, forty times!] It would be well done.

I estimate that I would write five volumes [Charpentier will convince him to write three instead of five] - which are already fully armed and in line in my brain and my papers. Therefore, I turn to your experience and I appeal to your camaraderie to have your opinion and also your support. I will write to Goncourt and Zola [.

You saw [Maurice] Dreyfous for La Rue in London, didn't you? Do you want to see him for this great novel? I will not write to Zola or Goncourt until after your response. Write promptly, my dear Scholl, because I am adrift, and do not wait for it to get worse for the outlaw!

You see well what I dream of. You understand the advantage that an editor capable of sending 3 to 400 francs per month against a copy would have. I was told that Charpentier had acted in this way with Zola. So I am not talking to you about a novel or an article for L'Évènement, pushed by you and publishable one of these days.

] You have treated me as a comrade. I ask you as a comrade for advice, and if necessary, the assistance of a recommendation.[Hector] Malot, who has been extremely helpful and devoted to me, has just replied on this subject. But he does not know the place. Edited as he is by another - and besides, he is absorbed by his wife's illness.

] I extend my hand cordially to you. Put out a pole, an image of a handshake across the Channel at the end of yours! 1- Allusion to the manifesto of the 363.The declaration was drawn up on May 18, 1877 by Republican deputies to President Patrice de Mac Mahon, expressing their opposition to the policy he was pursuing and the appointment of the monarchist Duke de Broglie as Prime Minister, even though the majority of the Chamber was republican. The text, written by a friend of Gambetta, Eugène Spuller, received three hundred and sixty-three signatures. Threatened in 1871 for belonging to the minority in the Commune council (opposed to the dictatorship of a Public Safety Committee), Vallès fled to Lausanne.

He was then sentenced to death in absentia on July 14, 1872 by the 6th. Having found refuge in London since 1875, the journalist-Communard began at that time the writing of the first volume of his trilogy Jacques Vingtras: The Child. Halfway between an autobiographical and social novel, Jacques Vingrat is "the story of a sacrificed generation, defeated in June 1848, humiliated on December 2, 1851 and crushed in May 1871 [bloody week]". Bypassing censorship and inventing a double, Vallès created an original and controversial novel. The Child appeared for the first time in installments in the newspaper Le Siècle from June 28 to August 5, 1878 under the pseudonym La Chaussade.

Vallès's efforts with Georges Charpentier will pay off as the publisher publishes this first part in volume in 1879. The other two volumes of the trilogy will follow: The Bachelor (published as Memoirs of a Rebel) and The Insurgent, also published by Charpentier in 1881 and 1886 (posthumously). The proscribed journalist will find valuable assistance from Aurélien Scholl during his painful years of exile.

Met in the offices of the newspaper La Nymphe around 1854, the two men belong to the same generation, the Forty-eighters. At that time, Scholl is already a well-known journalist, appreciated for his often ironic pen. They frequent the same cafes, publicists, artists, and caricaturists of the time: Courbet, Daudet, Carjat, etc. They cut their teeth together at Le Figaro and never part ways, until the bloody defeat of the Paris Commune.

In the 1970 edition of EFR/Livre club Diderot, a letter addressed to Hector Malot dated November 6, 1877 mentions our letter: "I wrote after your letter to Scholl who had offered my volume La Rue in London to Dreyfous, who offered to publish it at the first clearing." Maurice Dreyfous, essayist, publisher, buyer of the Charpentier house, and friend of T. The letters to Aurélien Scholl are published by the newspaper L'Echo de Paris from February 17 to 26, 1885 as well as in Le Mercure de France - ed. This letter, which remained unpublished, is not included.