- Homepage

- Author

- Auguste Maquet (3)

- Beydts (louis) (4)

- Camille Mauclair (3)

- Charles De Gaulle (3)

- Charles Monselet (3)

- Charles Wagner (3)

- Chateaubriand (5)

- Colette (4)

- Ernest Daudet (3)

- Jean-léon Gérôme (5)

- Julien DuprÉ (3)

- Louise Read (4)

- Marcel Proust (5)

- Paul Chabas (4)

- Paul Meurice (3)

- Proust (3)

- Roger Martin Du Gard (4)

- Salomon Reinach (3)

- Sully Prudhomme (7)

- Violette Leduc (4)

- Other (4052)

- Binding

- Era

- 18th Century (11)

- 1900 To 1960 (64)

- 1930s (4)

- 1960s (5)

- 1970s (7)

- 19th (5)

- 19th Century (49)

- 20th Century (16)

- Beautiful Era (12)

- Belle Epoque (49)

- First Empire (10)

- Nineteenth (19)

- Nineteenth Century (11)

- Post-war (23)

- Restoration (17)

- Revolution (5)

- Roaring Twenties (28)

- Second Empire (21)

- Second World War (6)

- World War Ii (9)

- Other (3757)

- Language

- Subject

- Type

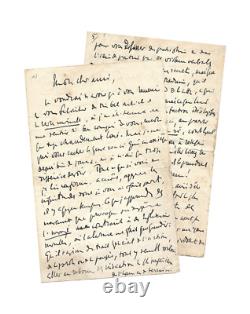

Charles MAURRAS / Signed Autograph Letter / Santé Prison / Léon Blum

Autographed letter signed "Ch Maurras" to Thierry Maulnier? [Paris] Prison de la Santé, April 19, 1937, 8 pp. In-8° Creases at the folds, scattered foxing, numerous redactions.

A long and abundant unpublished letter written from his cell in the prison of La Santé. "Thus, the nationals are not sufficiently accused of wanting, out of party spirit - and to sabotage the holy Blum experiment, all the elements of public prosperity. I would like to only thank you and congratulate you on the beautiful article in the Revue universelle, where I was glad to feel so well understood by you, although too warmly praised. But I cannot hide from you the great concern that has been troubling me for many days, and I have delayed this duty for too long. Everything I see and read confirms, increases, and exacerbates the worries I shared with you some time ago.

What I learn about the movements provoked or suggested by L'Insurgé compels me to new reflections, where the alarm only grows: whether it concerns the general nature of action, speech, or thought, everything seems to want to go against the most imperative indications of the hour and the terrain [.] While the form and nature of things work for us, and as one might expect, act against the criminal extravagances of those in power, you appear to want to create for them precisely what they lack, as a lifeline, the pretext and means for an offensive diversion of pure politics against the nationals. Do not suppose that I have ever imagined that good should happen by itself, nor that France's affairs would be restored without a strong, courageous, bold initiative from faithful Frenchmen. But it is clear, very clear, that if in a short time, the favorable, material and immaterial conditions had the greatest chance of being gathered in our hands or within our reach, a large, growing portion of public opinion, discontented, disappointed, irritated, would tend to form against the public wrongdoers, and as by good fortune the excuses they have prepared, the accusations they relied upon explode in their hands, as happens even, at unexpected points, certain rumors that threaten them, and that elsewhere a certain neutrality, an indifference seems to replace enthusiasm, the moment approaches to place an energetic affair. But you do not await this moment.

You leave before having secured this serious and precious chance that ensures the almost all-powerful support of a complicit atmosphere that multiplies effects for bold and enterprising minorities: and you do not even take the elementary precaution of legitimizing a passionate and ardent action by a lucid appeal to the public interest. You seem to savor a malicious pleasure or a perverse joy in disturbing the conscience and sentiment. Is it a literary exercise? Are you treating public spirit like the philistines of 1830? What profit will you gain by turning it against yourself? You are challenging it, roughing it up, turning it back! Thus, the nationals are not sufficiently accused of wanting, out of party spirit - and to sabotage the holy Blum experiment, all the elements of public prosperity: you imagine turning against the Exposition! Thus, the nationals are not sufficiently accused of lack of patriotism Delbos was returning to this last night in Carcassonne! Or that they will be called hitlerians tomorrow. Of internal emigrants, successors, and continuators of the army of Coblenz - [.] because they must denounce the dirty and bloody tricks of Cot. You are still doing what is in your power to free yourself from patriotism and the idea of homeland through verbal violence whose secret meaning can be discerned, but which the adversary is not obliged to translate, which he will take and does take literally, which is fair game, after all, but which allows them to place you among the ideological factions between which Europe is divided, to the party of "France but," of "France if," against which we have had so much trouble in reacting before! You give them, you hand over the name of the homeland: be assured, they will take it, admiring the simplicity of your gift!The moral work of our forty years of labor thus risks being undone, and why? For the most false of maneuvers and the most disastrous of excursions. For (and this is indeed the worst) these are not just words. I cannot close my eyes to the consistent testimonies, the evident signs of your close relations with the most dangerous hooded men. It is neither for me, nor for our leading friends of the A.

that I speak of danger. We are free from it, thanks to the repeated public warnings. We have so clearly disassociated ourselves from any confusion with these unfortunate, manipulated or manipulators.But, my dear friend, assuming you defend us from trembling for you, there are those you are leading! A brave youth can respond to the calls of voices and gestures, slipping into the most dubious, the vilest of plots! They do not yield to the allure of mysterious unknown leaders: they undergo the influence of your name, the prestige of your pen and, I must also tell you, the authority and friendship that publicly bind us, you and us. Nothing pains me more than to write this, but I would be guilty of silence, and I must ask you to quickly and publicly tear yourself away, stating why, from disastrous ties.

I ask this for the salvation of a certain number of young Frenchmen whose fate is partially attributable to you and for whom we bear, to a certain extent, responsibility. I have difficulty, moreover, in understanding how you do not see this duty both in thought and action, and how you do not already feel the physical horror of the trap into which you are leading, unwittingly, your generation. Physical, I say, for the trap is already tangible or felt! Be brave and even reckless for yourself as long as you wish: but the primary task of a leader is to care for his men and not to plunge them, heads down, into the mined dead end where they are awaited by the bulk of the enemy's force! If you do not see it, nor feel it, we must see it for you. It is not possible for the Action française to delay any longer the choice that imposes itself between its direction, its destiny, its national obligation, - and the troubled milieu where so many suspicious figures circulate and where so many resources are no less dubious. Especially now that the good minds and noble hearts whose intentions I know are precisely, very regularly, very methodically induced and swept to do and say exactly the opposite of what should be done and of what the obvious circumstances would require of them. This confusion and this risk of civil catastrophe cannot last.I ask you to reflect seriously and to tell me what your choice is. The bad one, which I cannot believe you capable of, would be tragic. Receive, my dear friend, the assurance of my warmest friendship, I have never given you a more certain proof of it than in this letter, Ch Maurras, Prison de la Santé, April 19, 1937." Condemned for publicly threatening Léon Blum with death in L'Action Française, Maurras was imprisoned in La Santé prison from October 29 to July 6, 1937. It was during this period that he wrote Mes idées politiques.

The royalist periodical founded in 1920 by Jacques Bainville and Henri Massis, La Revue universelle aimed to be close to L'Action française with renowned collaborators, including Jacques Maritain, Léon Daudet, Thierry Maulnier, Robert Brasillach, and Charles Maurras himself. The magazine focused mainly on foreign policy issues. During the war, it supported the Vichy regime and ceased publication in 1944. In 1974, the publication reappeared under the direction of François Natter with the name Revue universelle des faits et des idées. This letter appears to be addressed to Thierry Maulnier in response to his article (Les Essais / Charles Maurras et les deux grandeurs) in La Revue universelle from April 15 preceding.

Complete scan of the document available upon request.