- Homepage

- Author

- Auguste Maquet (3)

- Beydts (louis) (4)

- Camille Mauclair (3)

- Charles De Gaulle (3)

- Charles Monselet (3)

- Charles Wagner (3)

- Chateaubriand (5)

- Colette (4)

- Ernest Daudet (3)

- Jean-léon Gérôme (5)

- Julien DuprÉ (3)

- Louise Read (4)

- Marcel Proust (5)

- Paul Chabas (4)

- Paul Meurice (3)

- Proust (3)

- Roger Martin Du Gard (4)

- Salomon Reinach (3)

- Sully Prudhomme (7)

- Violette Leduc (4)

- Other (4052)

- Binding

- Era

- 18th Century (11)

- 1900 To 1960 (64)

- 1930s (4)

- 1960s (5)

- 1970s (7)

- 19th (5)

- 19th Century (49)

- 20th Century (16)

- Beautiful Era (12)

- Belle Epoque (49)

- First Empire (10)

- Nineteenth (19)

- Nineteenth Century (11)

- Post-war (23)

- Restoration (17)

- Revolution (5)

- Roaring Twenties (28)

- Second Empire (21)

- Second World War (6)

- World War Ii (9)

- Other (3757)

- Language

- Subject

- Type

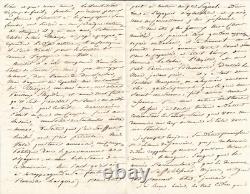

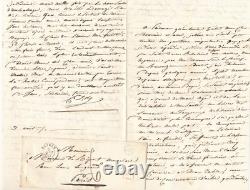

Anne Marie de MARGUERYE Countess HAUTEFEUILLE 11 signed autograph letters

A little-known woman of letters. Very young, at the age of 15, she was forced to marry Count Eugène Texier d'Hautefeuille.

The latter, starting in 1808, committed himself to the Napoleonic battlefields and the Restoration. Not returning, she separated from him in 1814. She then lived in solitude in her castle in Agy, a few kilometers from Bayeux.

Gustave Desnoiresterres, in a book dedicated to Balzac, recounts the story of this countess who, after her divorce, was later abandoned by her lover, Count Guernon-Ranville, who preferred a marriage of convenience. Balzac partially based the character of La Femme abandonnée on her (La Femme abandonnée, edition presented, established, and annotated by Madeleine Ambrière-Fargeaud, Paris, Gallimard, Folio classique, 2018).

From 1827, she spent a few years in the former convent of the Abbaye-au-Bois, where Juliette Récamier also occupied an apartment. The countess then returned to her properties in the provinces.This Countess d'Hautefeuille should not be confused with Anne Albe Cornélie d'Hautefeuille, born Beaurepaire (1789-1862), Countess Charles d'Hautefeuille, also a woman of letters, who published several works at the same time under the pseudonym Anna-Marie, including L'Âme exilée. Rich correspondence of friendship and business.

With fragile health, the countess suffers from loneliness and regularly relies on the marquis for help. Upset, she only writes now because she has not heard from her correspondent, the Marquis de Ripert-Monclar, for a long time, and complains that she had no address to write to him.

She thought this absence of news was due to their age difference. She would also like to submit some ideas to him. March 15, 1839, 2 pages. Sending address and postal marks. The countess realized that she had sent her business letter to the wrong number on the street.

His lack of response had hurt her. September 10, 1839, 2 pages.

She still has health problems: "This trip must heal me, at least restore me, or I am lost," and she must consult a doctor. She mentions a meeting in Paris and the anticipation of a letter: "a blank sheet" from the marquis, and then she would go there.October 19, 1839, 5 pages. It was agreed that the marquis's silence would be "a proof of adherence to the request for a loan of three thousand francs that I asked you to facilitate and which is essential for my undertaking." It is later understood that she must carry out repairs on a property for sale, the cost of which has burdened all her income. To meet her needs, the countess will sell several properties throughout her life. She continues to mention once again a meeting in Paris with a doctor who will convey news of her health to the marquis, which, for many years, would have required sacrifices she did not have the courage to make.

And she asks herself: "Oh, why have friends (for I have some very sincere ones), why do some relatives, though distant, not foresee that reducing me to this state of solitude, which no longer rests my vital chances on anything but annihilated forces or leads me to the end of a life that is dear to them? Why was my will not forced in time?Why am I now obliged, when the guarantees of success are so uncertain, to impoverish myself under those weaker than I to embrace the only path of salvation that remains to me? She should have taken advantage of the rays of friendship like those of the Marquis de Ripert-Monclar, "but by a cruel fate, those who were full of good will towards me were not free to express it to the necessary degree, and where this goodwill was less essential, customs, conventions, what is good, what is not intimidated and hindered me, reducing me to the most dangerous inaction.

Alas, for the unfortunate placed in the position I find myself in, it is thus possible, it is thus conceivable only to die. She informs him that she is leaving for the South. She is concerned about the marquis's health.July 2, 1842, 3 pages. She learns that the marquis has definitively left Paris for Avignon without notifying her while they are in business and friendship relations! She wrote him a letter that was returned to her in which she said she was depositing a sum of money in Paris. She again mentions the box that is to be sent to her containing her portrait and that of the Countess d'Hautpoul, which she values greatly. The countess shares the worries of the few distant relatives and friends she has left due to her absolute isolation given her age and delicate health.

For five years, she had the help of a Pole, a family man, "suffering from wounds and sadness," who lived under her roof. He acted as a factotum and made conversation with her "as best he could." He could also shoot a gun, "a precious skill for a woman living in the countryside without family." This man, having recovered, returned to active life and was replaced by another man in the "security position," but he turned out to be "lazy and stupid.

" She asks him to send her, if possible, an assistant who could replace him, a man above all honest. She finally received the portraits, including that of her "poor old friend who has been dead for a long time" (the Countess d'Hautpoul). This letter discusses the repayment of loans to Ripert-Monclar. She is delighted with the planned trip of Ripert-Monclar to Paris.

She names two people in the letter and did not understand whether they would also be in Paris or not. She asks him to convey her warm regards to them. January 8, 1846, 4 pages.

"A new neuralgic suffering and troubles in the position of abandoned isolated women have prevented me until now, my dear Amédée, from replying to your reassuring missive." The countess is grateful for the assurance of the fulfillment of a "good and friendly project," but still fears that it may not happen in Paris after "such a sweet and good hope." She writes that she has a "heavy heart" and feels "completely discouraged.

" Regarding a small accident she suffered: "I thank you for your concern for this painfully lax wrist of mine of which I told you about the suffering (...), it is from having lifted a too-heavy flower pot from the bottom of a frame that I sprained it." She compares the nature probably in Avignon where the marquis has settled, "sun, greenery, still roses," to the Norman nature where she lives: "we have only a cloudy sky, dark woods, and above all a damp ground where only ferns abound," and concludes: we have "the flowers of the earth, you have the flowers of life." She harshly criticizes Normandy, her country, that of "selfishness," "greed," and "malice." For those who remain, "one must not only grieve in the face of the rigors of nature, but one must also lament the analogies that the frosts entail and take everything, ice as well as salt." She concludes: "In this sad country, one is born dead, less the suffering! You will find me very sad today, but with you, I am what I am. She has not given news: "a flu effect, domestic troubles, sad news threatening impending disasters, this is what has mistreated, tormented, and afflicted me to the point that I delayed a response." She inquires about the health of the marquis and, when he is recovered, invites him to her home: "come again and come quickly" for a "cure of friendship, but this pleasure will be compensated by your well-being, and even if you were as robust as a fat ox, seeing you will always be seeing you.

" This would also be an opportunity to discuss business. More surprisingly, she has heard about his mother: "It has been centuries since I heard about my mother" and asks him, who has connections, to obtain some more precise information: "Although separated by very serious causes, the absolute ignorance of such close ties is always painful." In postscript on the edge of the fold: "I am very sad (...), the opportunity of your friendly visit will do me good.